Castro's Claim:

A Wagga Butcher's Claim for the Tichborne Fortune

The story of Castro, alias Orton, is one that ought to begin "Once upon a time"[1]

Roger Charles Doughty Tichborne was the eldest son born to Sir James Tichborne and his wife Henriette Felicité, and was heir to the family's ancient estates in Hampshire, England. Roger, a foppish mummsied Parisian boy[2] described by contemporaries as 'all narrowness', went missing in 1854, when Bella, the ship on which he was travelling, vanished en route from Rio de Janiero to New York.

Although Roger (and the entire crew) was officially declared lost at sea, his mother never stopped believing that her beloved son was alive. After contacting a clairvoyant, who assured her of Roger's wellbeing, Lady Tichborne began advertising for the whereabouts of her son in newspapers throughout the world. In Australia she eventually made contact with Arthur Cubitt, proprietor of the Missing Friends Office in Sydney, who placed further advertisements on her behalf in the colonial press.

Her efforts were not in vain. In 1866, 11 years after his disappearance, the unthinkable happened - 'Sir Roger' reappeared. Living in Wagga Wagga, a Riverina town of approximately 1,000 residents, the reputed long-lost heir was eking out a living as a butcher in Gurwood Street.

By all accounts Tom Castro, as he was now known, had little in common with the man he claimed to be. Tipping the scales at 18 stone (114 kg), one Wagga customer remembered Castro as 'loose and slommicking'. Later contemporaries described him as a 'mere mountain of flesh'[3], 'a bloated aristocrat'[4] and most unflatteringly, 'a mass of tastefully ornamented whale blubber in broadcloth'[5].

Wagga Wagga and Riverina residents knew the name Tom Castro many years prior to his international recognition as the infamous Claimant. The Honourable James Gormly first met Castro in Deniliquin in 1863, where he was employed as a journeyman butcher. After this, he relocated to Hay and worked as a slaughterman for "Parramatta Jack" Ward.

Tom Castro moved onto Wagga Wagga in 1864, when Gormly offered him work. However, he was primarily attracted to the town by 1864's Champion Race for £1000. After leaving Gormly's employment, Castro set up butchering in Gurwood Street premises, but was not long in this business before he went broke. Fortuitously, he met solicitor William Gibbes (who believed the butcher was really Roger Tichborne living incognito), and the rest is history.

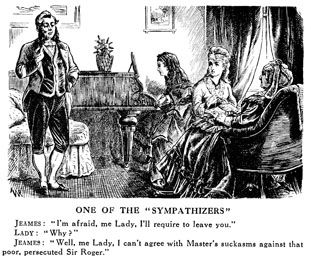

As the Tichborne Trials lumbered on in England, the disputed identity of Castro polarised the Wagga Wagga community. Some businessmen, including James Gormly, Richard Heydon and William Cottee did not support his claim to the Tichborne Estates, believing him to be a cunning impostor. However, other equally prominent businessmen like George Forsyth and James Warby supported Castro's claim, and in the end, were all the poorer for it, financially at least.

There were obvious discrepancies between the two men. Sir Roger was wan, effeminate and predominately French in his mannerisms, while Tom was stout, uncouth and had no understanding of his supposed native tongue. However, when mother and 'son' finally met in Paris, Lady Tichborne immediately professed motherly affection for the Wagga local, excitedly stating 'he looks like his father, and his ears look like his uncle's!'

Tom (now calling himself Sir Roger) found himself in greatly altered circumstances to which he had been living in Wagga. Following the public acknowledgment of Lady Tichborne that he was indeed her long-lost son, Tom and his family moved in with her, and he received an annuity of £1,000. The Tichborne heir was now ready to reclaim his inheritance.

This was not a straightforward affair. With father James, younger brother Alfred and officially Roger himself deceased however, rights to the Tichborne estates had passed to Alfred's infant son, Henry. For this situation to be reversed, Tom (hereafter known as 'The Claimant') needed first to prove unequivocally his identity in a court of law. In order to take his place as the legal heir to the Tichborne family's seat, Roger's friends, family and associates would have to be convinced he was indeed Roger, returned from his watery grave.

Pictures:

Above - Sir Roger Tichborne

Right - Tom CastroMichelle Maddison, curator

R. Storry Deans, Notable Trials: Romances of the Law Courts, Cassell & Company: London, 1906[2]

Robyn Annear, The Man Who Lost Himself: The Unbelievable Story of the Tichborne Claimant, Text Publishing: Melbourne, 2002[3]

Dr. E.V. Kenealy[4]

Arthur Lloyd, music hall star[5]

Attributed to G.A. Sala (English newsman) c. 1871-73

He would have won "if only he could have kept his mouth shut". [1]

Castro and his supporters set in motion one of the greatest cases of disputed identity in modern history. The baronet butcher of Wagga Wagga was about to become a cause célèbre in the English speaking world, and a small provincial Australian town was to be catapulted onto the international stage.

Nearly 4 years elapsed before the Claimant began his suit of ejectment against the trustees of the infant Sir Henry Tichborne, in a civil trial beginning on 11 May 1871.

In readiness for this, the Claimant and his camp had amassed an impressive array of witnesses who supported his claim. These included former servants of Sir Roger's, old brother-officers (of the Carbineer regiment to which Roger had belonged), friends and tenants of the Tichborne family, magistrates and even the family solicitor. 100 people swore under oath that the man standing before them was Sir Roger returned home at last. The 17 witnesses arraigned against him disagreed, and ultimately, swayed the case in the Tichborne family's favour.

The case was lost on a number of points. Castro could neither speak nor understand French, and unlike Roger, he had no tattoos. In hindsight, the Claimant admitted his cause was lost due to his inability to answer questions relating to his own past!

The trial lasted 102 days, and cost the Tichborne family over £91,000. Chief Justice Bovill declared his belief that the Claimant was guilty of wilful and corrupt perjury. Castro's immediate arrest followed, and he was transported by his own brougham to Newgate Gaol. Upon arrival, he was greeted by massed crowds cheering Sir Roger!, Arthur Orton! and even Wagga Wagga! in support of him.

After a month in prison, the Claimant was released on £10,000 bail, raised by his ever-faithful supporters. The intervening 12 months were spent by the Claimant travelling the country and drumming up support for his cause by competing in pigeon shoots and participating in lecture tours.

On 22 April 1873, the criminal trial against the Claimant began at Queen's Bench.

The prosecution had settled on 3 main counts of perjury against Castro: the statement made by him that he was Sir Roger Tichborne; the statement that he had seduced his cousin (Sir Roger's love interest, Katherine Doughty) and the statement that he was not Arthur Orton (the English alias of Thomas Castro).

The evidence against Castro was conclusive and overwhelming. Half of Wapping (Orton's home town) stepped forward to identify 'Sir Roger' as Arthur Orton, a local butcher. From Australia, there was also incontrovertible evidence gathered proving that Orton and Castro were one in the same person.

The trial lasted 188 days, cost the Crown £50,000 and saw 210 witnesses called for the prosecution. The summing up alone lasted 20 days. Finally, on 20 February 1874 the specially chosen jury returned their verdict - the defendant was not Sir Roger Tichborne, he was Arthur Orton. The Claimant was sentenced to 14 years penal servitude.

Once behind bars, the Claimant's popularity continued. However, as time passed, his support from outside gradually declined, and the general public soon forgot him.

Michelle Maddison, curator

Bram Stoker, Famous Impostors, Sturgis & Walton: New York, 1910

It was out of the midst of his humble collection of sausages and tripe that he soared up into the zenith of notoriety [1]

During the Trials public interest in the Claimant was enormous. His story was the subject of a Christmas pantomime, and the British public became accustomed to his face when his wax likeness was exhibited in Madame Tussaud's London Waxworks.

Tichborne Trial souvenirs flooded the market as the Claimant's infamy and popularity were capitalised upon. The British public could purchase a wide range of Tichbornalia, including cartoons, candleholders, medallions, ballads, broadsides, tea and tablecloths, handkerchiefs, crockery sets, children's toys and even slippers. In addition, popular artistes updated their acts with Tichborne gags, commemorative comic songs were penned, and dances such as the Tichborne Gallop were enjoyed by all.

One of the most affordable souvenirs was the Carte de Visite photographs that were mass produced for an eager public. Depicting key players in the Tichborne saga, these became collectors' items, and in popularity, even surpassed those of royalty. Some souvenirs were however, created exclusively for those with a disposable income. Most notably, a pressed glass plate depicting Arthur Orton, the Trial at Bar volumes (compiled by Dr. Kenealy) and a number of figurines - made in plaster, terracotta and china.

The Claimant's popularity had a greater impact upon British society than the mere production and dissemination of commemorative trinkets. Social upheaval and unrest (particularly amongst the upper classes) and even class conflict ensued during and after the Trials. As a result, British society was polarised into opposing groups - those who believed the Claimant was Sir Roger, and those who didn't. Public sentiment stood in favour of the Claimant, and against the Tichborne family (and the Establishment as a whole). The lower classes saw the Claimant as one of their own - being unjustly treated and ostracised by the ruling elite. The upper classes viewed him as a person who had violated every tradition of good breeding. Furthermore, amongst detractors, his great weight[2] became fodder for endless jokes and ridicule.

In class-conscious Britain, tensions were already simmering under the surface - between the poor and working classes, the middle, upper classes and gentry. These were brought to boiling point by Castro's claim to the Tichborne estates. According to Arabella Kenealy[3], "During the Trial personal bias ran so high that parents and children were estranged forever, life-long friendships made and severed, political factions and commercial and social alliances sealed and sundered - feuds of every magnitude bred and fostered"[4]

Kenealy himself, one of the greatest personalities of the Trial, behaved more like a partisan to the Tichborne cause than the esteemed lawyer he was. His actions throughout the trial (in defence of Castro) were so impassioned; they led to his being disbarred.

In 1884, Arthur Orton was released from Dartmoor Gaol, having served 10 years 4 months of his sentence. He was barely recognisable - thinner, and much healthier in appearance. Whereas his 1874 conviction had created enormous excitement throughout the country, his release elicited little comment. After lecture tours, printed confessions (which he later retracted), a stint as a peep show oddity, a music hall performer, and even as a bartender in the United States, Orton died in poverty in 1898.

Buried in a pauper's grave in Paddington Cemetery, London, one last act of defiance marked his passing. With the Tichborne family's permission, his coffin was engraved 'Sir Roger Charles Doughty Tichborne'.

Over a century has passed since the great Tichborne Trials. Today, this episode has the distinction of being one of the longest running court cases in British history. In terms of popular culture, they will forever be remembered as an unbelievable story which inspired artists, authors and historians, and ensured a spot for the butcher of Wagga in the annals of history. Michelle Maddison, curator

Mark Twain, Following the Equator: A Journey Around the World, Chapter XV, 1896

[2]By 1872, the Claimant's weight had ballooned to 388 pounds (176 kilograms)

[3]Daughter of Dr E.V. Kenealy, Defence Counsel for the Tichborne Claimant

[4]Arabella Kenealy, Memoirs of Edward Vaughan Kenealy LLD, 1908